Second-Order Optimization Methods: Beyond Gradient Descent

Introduction

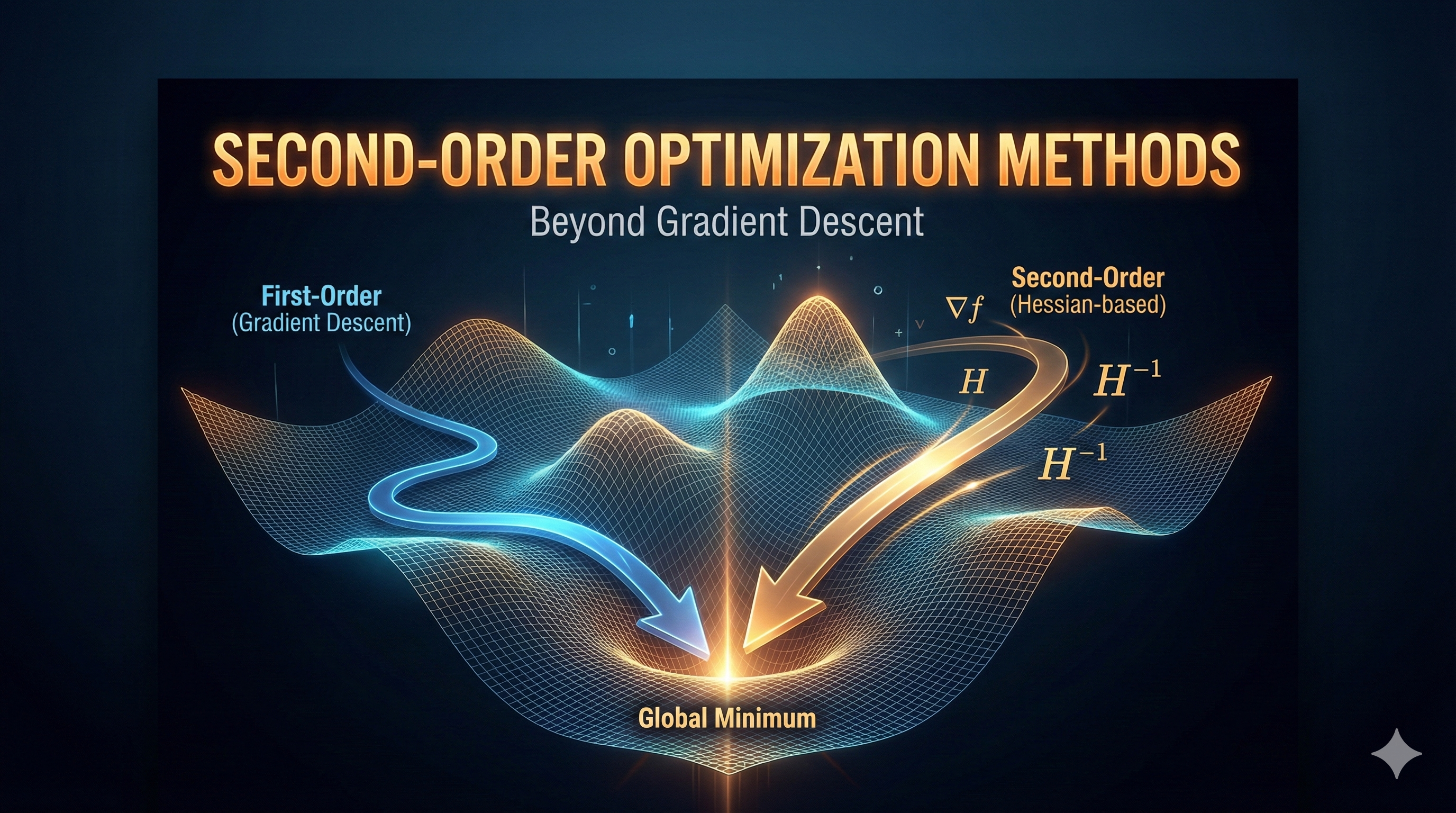

While first-order methods like SGD and Adam dominate deep learning, second-order optimization methods offer powerful alternatives by exploiting curvature information from the loss landscape. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore when and how to use these sophisticated techniques.

Key Insight

Second-order methods use the Hessian matrix (second derivatives) to understand the curvature of the loss function, enabling faster convergence with fewer iterations - though at higher computational cost per iteration.

The Limitation of First-Order Methods

Recall that gradient descent uses only the first derivative (gradient):

\[\theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \alpha \nabla J(\theta_t)\]This approach has fundamental limitations:

- No curvature awareness - treats all directions equally

- Slow convergence in ill-conditioned problems

- Requires careful learning rate tuning

- Oscillates in ravines and valleys

graph LR

A[Optimization Landscape] --> B[First-Order: Gradient Only]

A --> C[Second-Order: Gradient + Curvature]

B --> D[Slow, Many Iterations]

C --> E[Fast, Few Iterations]

B --> F[Low Cost Per Iteration]

C --> G[High Cost Per Iteration]

style B fill:#ff6b6b

style C fill:#6bcf7f

style D fill:#ffd93d

style E fill:#95e1d3

Newton’s Method: The Foundation

Mathematical Formulation

Newton’s method uses a second-order Taylor approximation of the loss function:

\[J(\theta) \approx J(\theta_t) + \nabla J(\theta_t)^T (\theta - \theta_t) + \frac{1}{2}(\theta - \theta_t)^T H(\theta_t) (\theta - \theta_t)\]Where $H(\theta_t)$ is the Hessian matrix:

\[H_{ij} = \frac{\partial^2 J}{\partial \theta_i \partial \theta_j}\]Minimizing this quadratic approximation yields the Newton update:

\[\theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - H^{-1}(\theta_t) \nabla J(\theta_t)\]Intuition: Adaptive Step Sizes

The Hessian inverse $H^{-1}$ acts as an adaptive learning rate matrix:

- Large curvature (steep valley) → small steps

- Small curvature (flat plateau) → large steps

- Negative curvature (saddle point) → direction reversal

This is fundamentally different from first-order methods which use a scalar learning rate!

Python Implementation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

import numpy as np

from typing import Callable, Tuple

from scipy.linalg import cho_factor, cho_solve

class NewtonOptimizer:

"""

Newton's method for unconstrained optimization.

Uses second-order information (Hessian) for faster convergence.

"""

def __init__(

self,

damping: float = 1e-4,

max_iterations: int = 100,

tolerance: float = 1e-6

):

"""

Args:

damping: Regularization for Hessian (Levenberg-Marquardt)

max_iterations: Maximum optimization iterations

tolerance: Convergence threshold for gradient norm

"""

self.damping = damping

self.max_iterations = max_iterations

self.tolerance = tolerance

self.history = {'loss': [], 'grad_norm': []}

def optimize(

self,

f: Callable,

grad_f: Callable,

hess_f: Callable,

x0: np.ndarray

) -> Tuple[np.ndarray, dict]:

"""

Optimize function using Newton's method.

Args:

f: Objective function

grad_f: Gradient function

hess_f: Hessian function

x0: Initial parameters

Returns:

Optimal parameters and optimization history

"""

x = x0.copy()

for iteration in range(self.max_iterations):

# Compute gradient and Hessian

grad = grad_f(x)

hess = hess_f(x)

# Check convergence

grad_norm = np.linalg.norm(grad)

if grad_norm < self.tolerance:

print(f"Converged at iteration {iteration}")

break

# Regularize Hessian (Levenberg-Marquardt damping)

hess_reg = hess + self.damping * np.eye(len(x))

# Solve Newton system: H * delta = -grad

try:

# Use Cholesky decomposition for efficiency

c, low = cho_factor(hess_reg)

delta = -cho_solve((c, low), grad)

except np.linalg.LinAlgError:

# Fallback to regularized inverse

delta = -np.linalg.solve(

hess_reg + 1e-3 * np.eye(len(x)),

grad

)

# Line search (backtracking)

alpha = self._line_search(f, x, delta, grad)

# Update parameters

x = x + alpha * delta

# Track progress

self.history['loss'].append(f(x))

self.history['grad_norm'].append(grad_norm)

if iteration % 10 == 0:

print(f"Iter {iteration}: loss={f(x):.6f}, ||grad||={grad_norm:.6f}")

return x, self.history

def _line_search(

self,

f: Callable,

x: np.ndarray,

direction: np.ndarray,

grad: np.ndarray,

alpha_init: float = 1.0,

rho: float = 0.5,

c: float = 1e-4

) -> float:

"""

Backtracking line search (Armijo condition).

Args:

f: Objective function

x: Current parameters

direction: Search direction

grad: Current gradient

alpha_init: Initial step size

rho: Backtracking factor

c: Armijo constant

Returns:

Step size satisfying Armijo condition

"""

alpha = alpha_init

fx = f(x)

descent = grad.dot(direction)

while f(x + alpha * direction) > fx + c * alpha * descent:

alpha *= rho

if alpha < 1e-10:

break

return alpha

# Example: Rosenbrock function optimization

def rosenbrock(x):

"""Rosenbrock function: f(x,y) = (1-x)^2 + 100(y-x^2)^2"""

return (1 - x[0])**2 + 100 * (x[1] - x[0]**2)**2

def rosenbrock_grad(x):

"""Gradient of Rosenbrock function."""

dx = -2*(1 - x[0]) - 400*x[0]*(x[1] - x[0]**2)

dy = 200*(x[1] - x[0]**2)

return np.array([dx, dy])

def rosenbrock_hess(x):

"""Hessian of Rosenbrock function."""

h11 = 2 - 400*(x[1] - x[0]**2) + 800*x[0]**2

h12 = -400*x[0]

h22 = 200

return np.array([[h11, h12], [h12, h22]])

# Run optimization

optimizer = NewtonOptimizer(damping=1e-4)

x_opt, history = optimizer.optimize(

rosenbrock,

rosenbrock_grad,

rosenbrock_hess,

x0=np.array([-1.0, 1.0])

)

print(f"\nOptimal solution: {x_opt}")

print(f"Optimal value: {rosenbrock(x_opt):.10f}")

The Computational Challenge

Hessian Complexity

For a model with $n$ parameters:

- Gradient: $O(n)$ storage, $O(n)$ computation

- Hessian: $O(n^2)$ storage, $O(n^3)$ inversion

For deep learning models with millions of parameters, this is prohibitively expensive!

Warning: Scalability

A model with 1 million parameters would require ~4 TB to store the Hessian matrix in memory. This makes exact Newton’s method impractical for deep learning.

Quasi-Newton Methods: Practical Alternatives

L-BFGS: Limited-Memory BFGS

L-BFGS (Limited-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno) approximates the Hessian inverse using only gradient information from recent iterations.

Key Ideas

- Don’t compute Hessian - approximate $H^{-1}$ implicitly

- Use gradient history - store only last $m$ gradient pairs

- Two-loop recursion - efficient computation of search direction

Mathematical Framework

Instead of storing $H^{-1}$, L-BFGS maintains:

\[\begin{aligned} s_k &= \theta_{k+1} - \theta_k \\ y_k &= \nabla J(\theta_{k+1}) - \nabla J(\theta_k) \end{aligned}\]The Hessian inverse approximation is built recursively:

\[H_k^{-1} = V_k^T H_{k-1}^{-1} V_k + \rho_k s_k s_k^T\]Where $\rho_k = \frac{1}{y_k^T s_k}$ and $V_k = I - \rho_k y_k s_k^T$

Complete L-BFGS Implementation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

from collections import deque

class LBFGSOptimizer:

"""

L-BFGS optimizer with two-loop recursion.

Memory-efficient quasi-Newton method suitable for large-scale problems.

"""

def __init__(

self,

memory_size: int = 10,

max_iterations: int = 100,

tolerance: float = 1e-5,

line_search_max_iter: int = 20

):

"""

Args:

memory_size: Number of (s, y) pairs to store

max_iterations: Maximum optimization iterations

tolerance: Convergence threshold

line_search_max_iter: Max line search iterations

"""

self.m = memory_size

self.max_iterations = max_iterations

self.tolerance = tolerance

self.line_search_max_iter = line_search_max_iter

# Storage for gradient differences

self.s_history = deque(maxlen=memory_size) # Parameter differences

self.y_history = deque(maxlen=memory_size) # Gradient differences

self.rho_history = deque(maxlen=memory_size) # 1 / (y^T s)

self.history = {'loss': [], 'grad_norm': []}

def optimize(

self,

f: Callable,

grad_f: Callable,

x0: np.ndarray

) -> Tuple[np.ndarray, dict]:

"""

Optimize using L-BFGS.

Args:

f: Objective function

grad_f: Gradient function

x0: Initial parameters

Returns:

Optimal parameters and history

"""

x = x0.copy()

grad = grad_f(x)

for iteration in range(self.max_iterations):

# Check convergence

grad_norm = np.linalg.norm(grad)

self.history['grad_norm'].append(grad_norm)

self.history['loss'].append(f(x))

if grad_norm < self.tolerance:

print(f"Converged at iteration {iteration}")

break

# Compute search direction using two-loop recursion

direction = self._two_loop_recursion(grad)

# Line search

alpha = self._strong_wolfe_line_search(f, grad_f, x, direction, grad)

# Update parameters

x_new = x + alpha * direction

grad_new = grad_f(x_new)

# Update history

s = x_new - x

y = grad_new - grad

# Check curvature condition

sy = s.dot(y)

if sy > 1e-10:

self.s_history.append(s)

self.y_history.append(y)

self.rho_history.append(1.0 / sy)

x = x_new

grad = grad_new

if iteration % 10 == 0:

print(f"Iter {iteration}: loss={f(x):.6f}, ||grad||={grad_norm:.6f}")

return x, self.history

def _two_loop_recursion(self, grad: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Compute search direction using L-BFGS two-loop recursion.

This efficiently computes H^{-1} @ grad without forming H^{-1}.

Args:

grad: Current gradient

Returns:

Search direction

"""

q = grad.copy()

alphas = []

# First loop (backward)

for s, y, rho in zip(

reversed(self.s_history),

reversed(self.y_history),

reversed(self.rho_history)

):

alpha = rho * s.dot(q)

q = q - alpha * y

alphas.append(alpha)

# Initial Hessian approximation (scaling)

if len(self.s_history) > 0:

s_last = self.s_history[-1]

y_last = self.y_history[-1]

gamma = s_last.dot(y_last) / y_last.dot(y_last)

r = gamma * q

else:

r = q

# Second loop (forward)

alphas.reverse()

for s, y, rho, alpha in zip(

self.s_history,

self.y_history,

self.rho_history,

alphas

):

beta = rho * y.dot(r)

r = r + s * (alpha - beta)

return -r

def _strong_wolfe_line_search(

self,

f: Callable,

grad_f: Callable,

x: np.ndarray,

direction: np.ndarray,

grad: np.ndarray,

c1: float = 1e-4,

c2: float = 0.9

) -> float:

"""

Strong Wolfe line search.

Finds step size satisfying both Armijo and curvature conditions.

Args:

f: Objective function

grad_f: Gradient function

x: Current parameters

direction: Search direction

grad: Current gradient

c1: Armijo constant

c2: Curvature constant

Returns:

Step size

"""

alpha = 1.0

fx = f(x)

descent = grad.dot(direction)

# Simple backtracking (simplified Wolfe)

for _ in range(self.line_search_max_iter):

x_new = x + alpha * direction

fx_new = f(x_new)

# Armijo condition

if fx_new <= fx + c1 * alpha * descent:

# Curvature condition (simplified)

grad_new = grad_f(x_new)

if abs(grad_new.dot(direction)) <= c2 * abs(descent):

return alpha

alpha *= 0.5

return alpha

# Example usage

lbfgs = LBFGSOptimizer(memory_size=10)

x_opt, history = lbfgs.optimize(

rosenbrock,

rosenbrock_grad,

x0=np.array([-1.0, 1.0])

)

print(f"\nL-BFGS Optimal solution: {x_opt}")

print(f"L-BFGS Optimal value: {rosenbrock(x_opt):.10f}")

Natural Gradient Descent

The Information Geometry Perspective

Natural Gradient considers the geometry of the parameter space using the Fisher Information Matrix:

\[F(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{p(x|\theta)} \left[ \nabla \log p(x|\theta) \nabla \log p(x|\theta)^T \right]\]The natural gradient update is:

\[\theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \alpha F^{-1}(\theta_t) \nabla J(\theta_t)\]Why Natural Gradient?

Standard gradient descent is not invariant to reparameterization. Natural gradient uses the Riemannian metric defined by the Fisher matrix, making it invariant to parameter transformations.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

class NaturalGradientOptimizer:

"""

Natural Gradient Descent using Fisher Information Matrix.

Particularly effective for probabilistic models and policy gradient methods.

"""

def __init__(

self,

learning_rate: float = 0.01,

damping: float = 1e-4,

max_iterations: int = 100

):

self.learning_rate = learning_rate

self.damping = damping

self.max_iterations = max_iterations

def compute_fisher_matrix(

self,

log_prob_fn: Callable,

params: np.ndarray,

samples: np.ndarray

) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Compute Fisher Information Matrix empirically.

Args:

log_prob_fn: Log probability function

params: Current parameters

samples: Data samples

Returns:

Fisher matrix approximation

"""

n_params = len(params)

fisher = np.zeros((n_params, n_params))

for sample in samples:

# Compute score (gradient of log-likelihood)

score = self._compute_score(log_prob_fn, params, sample)

# Outer product

fisher += np.outer(score, score)

fisher /= len(samples)

return fisher

def _compute_score(

self,

log_prob_fn: Callable,

params: np.ndarray,

sample: np.ndarray,

eps: float = 1e-5

) -> np.ndarray:

"""Compute score function (gradient of log-prob) numerically."""

score = np.zeros_like(params)

for i in range(len(params)):

params_plus = params.copy()

params_minus = params.copy()

params_plus[i] += eps

params_minus[i] -= eps

score[i] = (

log_prob_fn(params_plus, sample) -

log_prob_fn(params_minus, sample)

) / (2 * eps)

return score

def update(

self,

params: np.ndarray,

gradient: np.ndarray,

fisher: np.ndarray

) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Natural gradient update.

Args:

params: Current parameters

gradient: Standard gradient

fisher: Fisher information matrix

Returns:

Updated parameters

"""

# Regularize Fisher matrix

fisher_reg = fisher + self.damping * np.eye(len(params))

# Compute natural gradient

try:

natural_grad = np.linalg.solve(fisher_reg, gradient)

except np.linalg.LinAlgError:

# Fallback to standard gradient

natural_grad = gradient

# Update parameters

params_new = params - self.learning_rate * natural_grad

return params_new

Comparison: When to Use Each Method

graph TD

A[Choose Optimization Method] --> B{Problem Size?}

B -->|Small n < 1000| C[Newton's Method]

B -->|Medium 1000 < n < 100k| D[L-BFGS]

B -->|Large n > 100k| E{Problem Type?}

E -->|Probabilistic Model| F[Natural Gradient]

E -->|General Deep Learning| G[Adam/SGD]

C --> H[Fast Convergence<br/>Few Iterations]

D --> I[Good Convergence<br/>Memory Efficient]

F --> J[Invariant Updates<br/>RL/Bayesian]

G --> K[Scalable<br/>Stochastic]

style C fill:#6bcf7f

style D fill:#95e1d3

style F fill:#ffd93d

style G fill:#ff6b6b

Decision Matrix

| Method | Best For | Pros | Cons | Memory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newton | Small-scale, convex | Quadratic convergence | $O(n^3)$ cost | $O(n^2)$ |

| L-BFGS | Medium-scale, batch | Fast, memory-efficient | Requires full batch | $O(mn)$ |

| Natural Gradient | Probabilistic models, RL | Parameter-invariant | Fisher computation | $O(n^2)$ |

| Adam | Large-scale, stochastic | Scalable, robust | Slower convergence | $O(n)$ |

Tip: Hybrid Approaches

Consider using L-BFGS for final fine-tuning after pre-training with Adam. This combines the scalability of first-order methods with the fast convergence of second-order methods.

Practical Applications

1. Logistic Regression with L-BFGS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

from scipy.optimize import minimize

def logistic_loss_and_grad(params, X, y):

"""Compute logistic loss and gradient."""

z = X.dot(params)

predictions = 1 / (1 + np.exp(-z))

# Loss

loss = -np.mean(y * np.log(predictions + 1e-10) +

(1 - y) * np.log(1 - predictions + 1e-10))

# Gradient

grad = X.T.dot(predictions - y) / len(y)

return loss, grad

# Use scipy's L-BFGS implementation

result = minimize(

fun=lambda w: logistic_loss_and_grad(w, X_train, y_train)[0],

x0=np.zeros(X_train.shape[1]),

method='L-BFGS-B',

jac=lambda w: logistic_loss_and_grad(w, X_train, y_train)[1],

options={'maxiter': 100, 'disp': True}

)

print(f"Optimal weights: {result.x}")

print(f"Final loss: {result.fun}")

2. Neural Network Fine-Tuning

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class LBFGSFineTuner:

"""Fine-tune neural network with L-BFGS."""

def __init__(self, model: nn.Module, max_iter: int = 20):

self.model = model

self.max_iter = max_iter

def fine_tune(self, train_loader, criterion):

"""Fine-tune model using L-BFGS."""

optimizer = torch.optim.LBFGS(

self.model.parameters(),

lr=1.0,

max_iter=self.max_iter,

history_size=10,

line_search_fn='strong_wolfe'

)

def closure():

optimizer.zero_grad()

total_loss = 0

for inputs, targets in train_loader:

outputs = self.model(inputs)

loss = criterion(outputs, targets)

loss.backward()

total_loss += loss.item()

return total_loss

optimizer.step(closure)

return self.model

Looking Ahead: Knowledge Graphs

While second-order methods excel at optimization, the next frontier in AI involves structured knowledge representation. In our upcoming series on Knowledge Graphs, we’ll explore:

- How to represent complex relationships between entities

- Graph neural networks for reasoning over structured data

- Combining symbolic knowledge with neural optimization

- Applications in recommendation systems, drug discovery, and NLP

Coming Soon

Our next post will introduce Knowledge Graphs fundamentals - representing the world’s knowledge as interconnected entities and relationships. We’ll show how optimization techniques (including those covered here) apply to learning graph embeddings!

Conclusion

Second-order optimization methods offer powerful tools for specific scenarios:

Key Takeaways

- Newton’s Method - Quadratic convergence but $O(n^3)$ cost

- L-BFGS - Practical quasi-Newton for medium-scale problems

- Natural Gradient - Geometrically principled for probabilistic models

- Hybrid Strategies - Combine first and second-order methods

When to Use Second-Order Methods

- ✅ Small to medium models (< 100k parameters)

- ✅ Batch optimization (full dataset fits in memory)

- ✅ Fine-tuning pre-trained models

- ✅ Convex or near-convex problems

- ✅ High-precision requirements

When to Stick with First-Order

- ❌ Large-scale deep learning (millions of parameters)

- ❌ Stochastic/mini-batch training

- ❌ Limited memory environments

- ❌ Highly non-convex landscapes

References

- Nocedal & Wright (2006). “Numerical Optimization” - The definitive reference

- Martens (2010). “Deep learning via Hessian-free optimization”

- Amari (1998). “Natural Gradient Works Efficiently in Learning”

- Liu & Nocedal (1989). “On the Limited Memory BFGS Method”

- Bottou et al. (2018). “Optimization Methods for Large-Scale Machine Learning”

Related Posts: